My Stasi File

The Decoding of Case File XV 5666/88

It was January 2021 and Berlin was in lockdown. The pandemic had severely restricted the pleasures of urban life. Businesses and institutions considered system-relevant kept their doors open to the public. These exceptions included chocolate stores, newsstands, wine shops and, of course, museums. A dark and cold Friday offered the perfect opportunity to visit Berlin’s own Stasi Museum. The Stasi, formally the Ministerium für Staatssicherheit or “MfS,” was the omnipresent secret police and intelligence agency of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), otherwise known as East Germany. The museum is housed in the former Stasi headquarters in Berlin Lichtenberg.

Entering the museum is like stepping back in time to East Berlin during the Cold War. The paneling, carpets, chairs, and telephones were left as they were when the Berlin Wall fell on November 9th, 1989. I was one of very few visitors that day. The large, silent and unpeopled exhibit space was decidedly eerie. I slowly walked through the exhibits, reading about the thousands of men and women whose lives were ruined by the secret police. I glanced at the Socialist Modern furnishings and found them at once aesthetically pleasing and creepy.

After I completed the tour, I felt shaken and proceeded to the museum café. I was served coffee and cookies on familiar-looking Soviet-era tableware. The coffee itself tasted like East German coffee in the 1980s. Or was that just my imagination? On my way out, I noticed a non-interactive information kiosk. Here the museum offered its guests the ability to order archival copies of individual Stasi files. I thought for a moment: Do I have a Stasi file? As I could not answer that question, I filled out the form, left the museum, and quickly forgot about the request.

Why would I have a Stasi file? In 1989 I was an exchange student in Tübingen, West Germany. Massive change was underway in Europe. Gorbachev challenged the post-war status quo, and revolution was in the air. I was a lazy student, but an active traveler. I took every available opportunity to visit Warsaw Pact countries in hopes of better understanding the shape of the transformation to come.

In Hungary, I befriended a group of young pro-democracy students. We drank, smoked and debated the future of our generation. I joined my friends in a protest march across the Chain Bridge in Budapest, which was expressly forbidden by the police. We were met with rows of police officers armed with batons. The police attacked the peaceful demonstrators with a savagery that was utterly unknown to me. I saw limp and bloodied bodies scattered on the ground. The police beat the demonstrators with an intent to seriously injure or kill. I was arrested and instinctively flashed my American passport. Once in custody, I was briefly interrogated by an English-speaking police officer. He listlessly asked about my presence at an illegal demonstration. I explained that I had mistakenly believed that I was participating in a folk festival. He accepted my implausible explanation without further comment. Later that evening the officer released me to the US Embassy, where I spent the night. I drank Heineken beer with several American soldiers my age. We watched a horror movie called Demon Seed. The soldiers did not ask me why I was there.

Shortly thereafter I spent a month in Warsaw, Poland, and connected with a group of young democratic socialists led by a charismatic psychoanalyst. I will call him Andrzej. He was charming, spoke perfect English, and always had a wallet full of western currency. He vehemently hated both the Polish Communist party and the trade-union movement, Solidarity, and had dreams of a democratic, socialist and independent Poland. I never heard anything about his work as mental health professional. Given his open schedule, it did not seem as if he managed a praxis or worked in a clinic. If I remember correctly, he considered himself to be a Lacanian. I sometimes wondered if Andrzej worked for the CIA. He was a mysterious figure and I admired him.

We met nightly in the lobby bar of the Forum Hotel. Despite being poor, we were able to live quite well trading West German marks and US dollars on the black market. We spent evenings sitting around a large table drinking beer and smoking local cannabis. The cannabis was simply overlooked by the hotel staff. I was told that they did not know what it was, but I assumed that Andrzej had paid them off. We were waiting for the first free elections in Poland in decades. The election proceeded and resulted in a victory for democracy. Unfortunately, our celebration ended in violence. On the night of the election, Polish police brutally beat our friend, Petri, who was a large, taciturn, Estonian poet. We assumed that the police were seeking revenge after their defeat. We picked Petri up from the hospital and arranged for new clothes, money and identification.

From my home in Tübingen I made several trips to Berlin to meet with East German friends. We were cautious, but not overly paranoid. One night at the Komische Oper, I was approached by a young woman, Frau A. Faust, and her three small children. She discreetly invited me to dinner at her home in a remote part of town. I accepted. We agreed to meet the next evening at the Friedrichstraße S-Bahn station. In my first-ever ride in an East German Trabant, she drove me to her place. The evening was an adventure in incomplete communication (bad English, bad German). The children were interested in music, movies and magazines that I had never heard of, but I did my best.

So perhaps I did have a Stasi file. I had completely forgotten about the application and was surprised to find a copy of my Stasi file mailed to my Berlin apartment. I scanned it briefly. I did not spend much time with the file, as I was put off by its many confusing and unfamiliar codes. Only recently did I decide to research the meaning of the codes. What I found was a deeper layer of significance and a tiny window into the dysfunction and brutality of the Stasi system.

Below is my attempt to decode and interpret an archived copy of my Stasi record from the Federal Archives (Bundesarchiv).

The Analysis

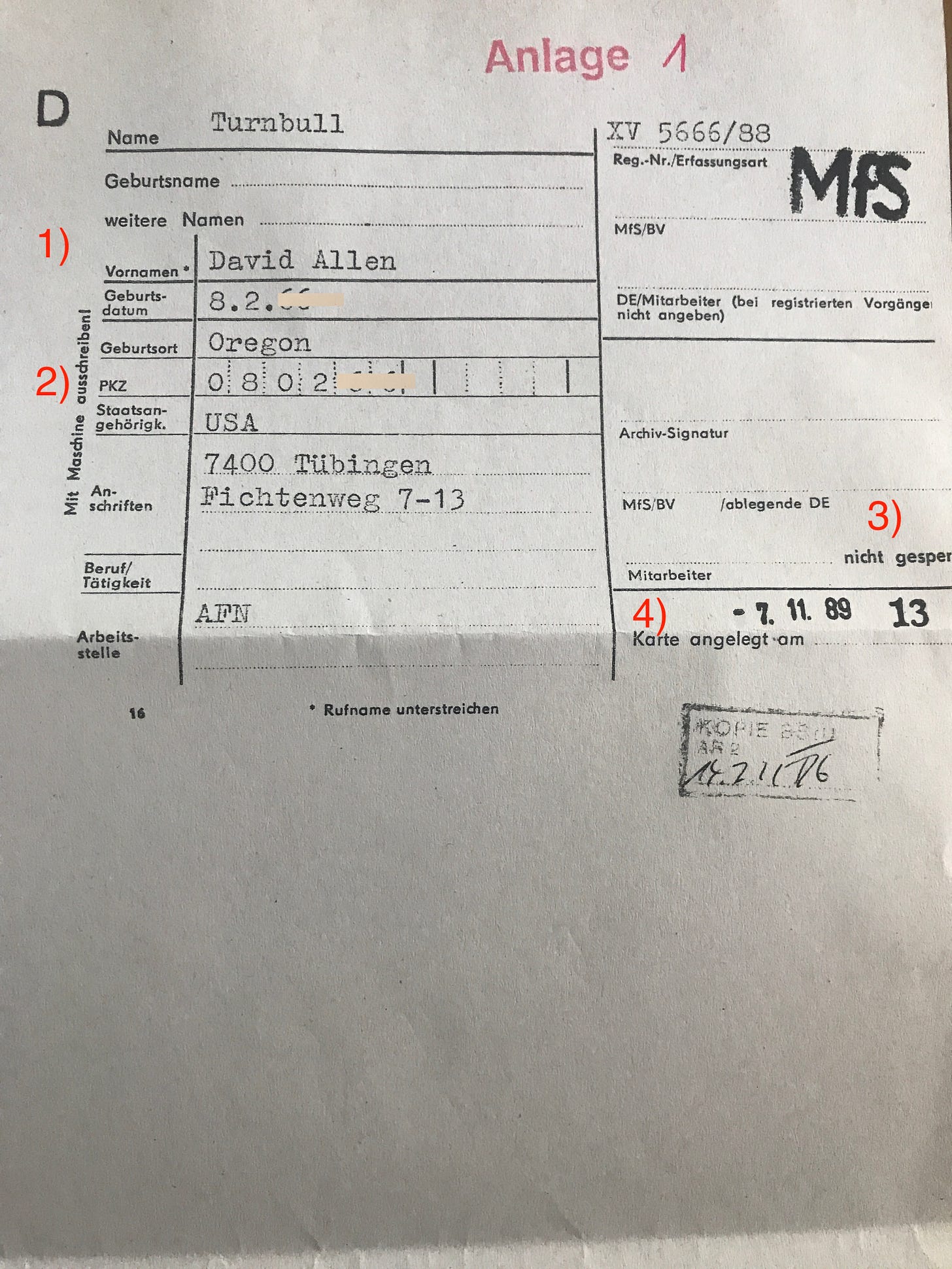

Attachment 1 (Anlage 1)

1) Attachment 1 displays my personal registration details. These details were easily gathered from the data entered on my visa application.

● Name: Turnbull

● First names: David Allen

● Date of Birth: 8.2.XX (February 8, 19XX)

● Place of Birth: Oregon, USA

● PKZ (personal identification number): The code is based only on my birthday. The blank boxes were reserved for birthplace and sequential numbers for those born on the same date. These extra spaces applied to GDR citizens. I have obscured my birthday out of data privacy concerns.

● Citizenship: USA

● Address: 7400 Tübingen, Fichtenweg 7–13

● Profession/Activity: AFN

For the record, I was not, and am not, a spy for the Armed Forces Network

According to my file, I worked for the Armed Forces Network (AFN), presumably as a spy. The AFN is a radio broadcast network that delivered news and music to the GDR and other Warsaw Pact countries. For the record, I was not, and am not, a spy for the Armed Forces Network. However, had I been offered that job in 1988, I would have accepted it without hesitation.

I was no conceivable threat to the German Democratic Republic. In fact, had the Stasi followed up on my address in Tübingen, they would have learned that I lived with a family as an au pair.

Also notable in this section is the introduction of my “registration number” XV 5666/88.

2) With reporting of foreign residence (Mit Meldung ausländischen Aufenthalt). The Stasi kept track of West Germans, and other foreigners, who were perceived as having some relevance for the East German state.

3) Not blocked (nicht gesperrt). As the file was not blocked, there were no restrictions on access.

4) File updated on (Karte angelegt am 7.11.1989). November 7, 1989 – This was the last database update of my file.

Consider this date for a moment. My file was updated two days before the Berlin Wall fell, and the German Democratic Republic de facto ceased to exist. In the last 48 hours of active Stasi employment, my case officer dutifully updated my file. Now that is dedication. Or madness.

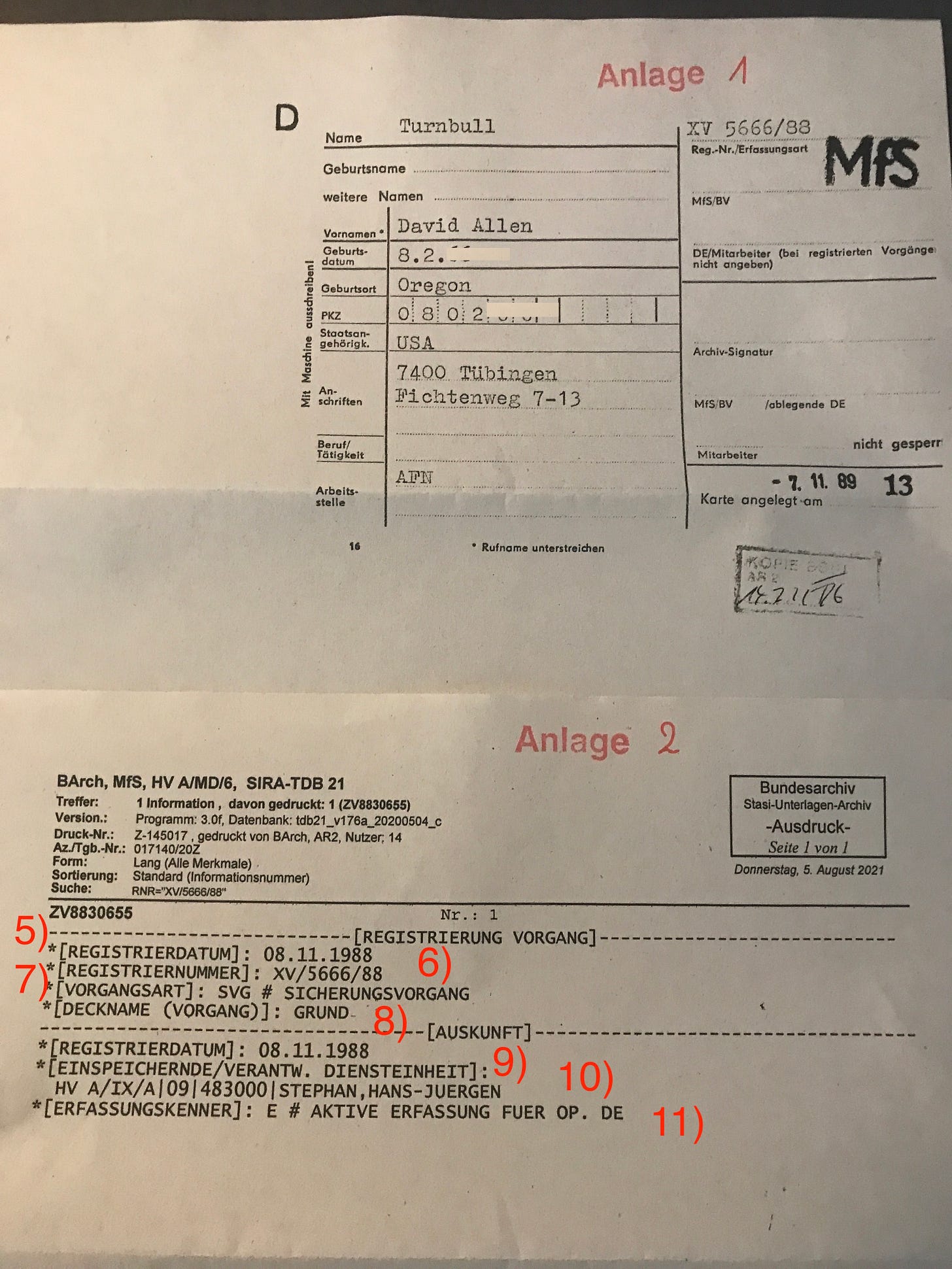

Attachment 2 (Anlage 2)

5) Date of Registration (Registrierungsdatum: 08.11.1988). The meaning of this entry is clear enough. On November 8, 1988, a case file was created for David Turnbull of Sweet Home, Oregon, USA. It is difficult to say exactly what the trigger was, but it was possibly the delightful dinner I had with Frau A. Faust and her three children. From the Stasi perspective, I covertly arranged to meet a young woman and her family with hostile intentions. On the following day, I boarded her Trabant outside of the Friedrichstraße S-Bahn station, whereupon she drove me to her home on the outskirts of Berlin in Schöneiche. This had to be the answer. From this day on, I was probably trailed during every visit. As an artist and a free spirit, it is likely that Frau Faust had already attracted Stasi attention and was closely monitored.

6) Registration number (Registrierennummer: XV 5666/88). I should get my Stasi registration number printed on a trucker hat. “XV” indicates the person in question was “operationally relevant” to the Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung (HVA), the foreign intelligence branch of the Stasi. Given the seriousness of the classification, it is possible that they took the AFN suspicions seriously at the time.

7) Type of Case. Security Case. Protective Operation (VORGANGSART SVG # SICHERUNGSVORGANG). This entry seems to suggest XV 5666/88 was an operative case file opened to protect an area, institution or person from “enemy activity,” particularly foreign intelligence influence. Given that I was an au pair at the time, this seems to be absurdly over-cautious.

8) Cover Name (DECKNAME). Unfortunately, I was not given a cover name, which suggests to me that they did not consider me to be particularly threatening after all.

9) Entering / responsible operational unit (EINSPEICHERNDE / VERANTW. DIENSTEINHEIT). For each Stasi file there is a corresponding department or service unit, as well as officers responsible for initiating and acting on the file. The operational unit would presumably have been the team assigned to monitor me.

10) Information source (HV A/IX/A |09| 483000). My record seems to come from the HVA (Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung), which was the Stasi’s foreign intelligence directorate. Department IX was responsible for “Information Management and Analysis” (Informationswesen und Auswertung), so essentially the unit responsible for processing the data. “09” may have been the file clerk code inside the department and “48300” may have been my personal entry number in the registry handled by HVA IX/A/09. Is that clear enough for you?

Oberstleutnant Hans-Jürgen Stephan was likely the officer who entered the data. I have tried without success to find Hans-Jürgen Stephan. I have found 13 obituary notices by that name and another 15 current telephone listings. The most prominent Hans-Jürgen Stephan is a compliance lawyer in Berlin who is roughly my age. There is another Hans-Jürgen Stephan who is active in Potsdam as a roofer. When I typed the name into Google Gemini, the system tauntingly suggested that Oberstleutnant Stephan was a “high-ranking” MfS officer, but no files or data were available.

11) Registration Code. Active Registration for Operational Service Unit

(ERFASSUNGSKENNER: E # Active Erfassung fuer OP. DE)

● “E” = Active Registration (Aktive Erfassung)

● “OP” = Operational Case (Operativer Vorgang)

The above codes suggest that I was actively registered in the Stasi’s operational intelligence database for use by an operational unit. Otherwise, I was apparently a person of interest or concern. In Stasi terminology, persons of interest might receive one of three categorizations:

1. “K” (Kontakthinweis), which means only contact information and not important.

2. “V” (Vorgangshinweis), meaning there is a note of suspicion.

3. “E” (Erfassung) means the person is flagged for active attention. I might assume from this designation that I was followed, and closely monitored, along with my friends.

What does it all mean?

For me personally, the file has no great significance. I was a tourist and a clueless one at that. I faced no serious threats or consequences. I was playing, without risk, with a terrible system that destroyed the lives of thousands, tore apart families and drove decent citizens into exile, prison or suicide. For former citizens of the GDR, the personal Stasi file is a vastly more serious and consequential matter. There is no equivalence between my youthful adventures and the suffering of innocent civilians. My motivation for writing about my Stasi file was an opportunity to explore some personal memories from distant time of bewildering change.

Was the German Democratic Republic insane or just too early?

It is easy to conclude that the obsessive monitoring of East German citizens and foreign visitors was self-destructive madness. Of course it was that. The efforts required to manually monitor hundreds of thousands of people, their conversations, their letters, their lovers, their favorite brands of cigarettes, and their opinions were not sustainable. That much is obvious. It is impossible to say whether the disproportionate spending on surveillance killed off the repressive regime or kept it afloat for an extra decade.

But what if the technology of 2025 was available to East Germany in 1961? The country’s totalitarian impulses would have been vastly cheaper and easier to implement, and potentially profitable. If Mark Zuckerberg reads books about the Cold War, he must get quite a laugh. While absolute surveillance and mass manipulation financially ruined the GDR, it has made billions in profit for Meta. If a country today chooses the path of totalitarianism, all the infrastructure it needs is firmly in place. Perhaps Erich Honecker, the last General Secretary of East Germany’s Socialist Unity Party, was less an idiot than a man born too soon.

This is such a cool read!